The Inquirer PR & History

Press Release – September

20, 2006

LONG version: 1970 words

by Koozma J. Tarasoff,

882 Walkley Road, Ottawa, Ontario K1V 6R5 Canada

Email: Tarasoff@spirit-wrestlers.com

Phone/fax: (613) 737-5778

Published in Nonviolence, Sept-Oct 2006. Journal of the The International Gandhian Institute for Nonviolence and Peace, Tamil Nadu, India.

LONG version: 1970 words

by Koozma J. Tarasoff,

882 Walkley Road, Ottawa, Ontario K1V 6R5 Canada

Email: Tarasoff@spirit-wrestlers.com

Phone/fax: (613) 737-5778

Published in Nonviolence, Sept-Oct 2006. Journal of the The International Gandhian Institute for Nonviolence and Peace, Tamil Nadu, India.

The Inquirer Revisited 50 Years Later

The former editor of The Doukhobor Inquirer and current Doukhobor published-author Koozma J. Tarasoff of Ottawa and Andy Conovaloff, a Molokan webmaster from Arizona, USA recently summarized the 1440 items written over 50 years ago and discovered a wealth of rich archival materials that have relevance to our day. Tables of contents for all 50 issues are now posted on the Internet at www.spirit-wrestlers.com in HTML format and as an Excel spreadsheet with keywords and summaries of each article. The original cover designs were added to make this an attractive yet informative research tool for the general public and the serious researcher.Although short-lived, The Inquirer monthly publication in Canada from 1954 to 1958 literally shook the Doukhobor community in North America. As a pioneering journalistic venture, the journal sought fresh ideas and worked to correct the popular inaccurate descriptions of the Doukhobors by the media. Through news reports, feature stories, editorials, satirical columns, human interest stories, book reviews, and Letters to the Editor, the publication fearlessly researched the history of their ancestors.

The Inquirer challenged the notion of leaders claiming special powers of being part ‘of the Divine Right of Kings’. On the basis of early history, its editors discovered that early leader Ilarion Pobirokhin in the 1700s succumbed to the notion of Kings, Queens and Popes to see himself as claiming a primogeniture right to some higher connection to God. His intent was power, paradoxically similar to the takeover of Christendom by Emperor Constantine I. It was early in the 4th century AD that Constantine robbed millions of people from pursuing the spark of God within each person and instead established a Church as a ‘permitted’ religion vested in one institution residing in Rome. The Inquirer reinstated the original notion of the God Within and dispensed with the phantom need for a church hierarchy.

Also The Inquirer challenged the concept of sectarianism. Since the 1895 arms burning, the Doukhobors ceased to be a sect and took on the characteristics of a social movement or a way of life. From the inside, the aim of the Doukhobors became deep, broad, and universal. From the outside, the church and state recognized them as a threat to the existing social order because their ideas were Tolstoyan in nature in that they were against patriotism and self-interest at the expense of others.

A third contribution to the understanding of society was the use of ‘zealotry’ for extremist behaviour. During the mid-1900s, the popular sensationalistic press tended to label all Doukhobors as people having almost genes of violence. The Inquirer challenged this in a study of the press by pointing out that those who participate in arson and bombing are arsonists and bombers. But they are not Doukhobors, even though they hide in hijack manner under the umbrella or cloak of the Doukhobors for protection and legitimacy.

Young people mostly students from the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon as well as High Schools desired to see themselves as worthy citizens in the new emerging society. The Inquirer was the first English language publication of Doukhobors in the world that stimulated its readers to think and question in the manner of Socrates of old: ‘That the unexamined life is not worth living.’

In reaction, some Canadian Doukhobor elders opposed the use of English in the journal. Until then, Russian was considered to be the official language of the group particularly because the elders were still close to the pioneering era when their parents and grandparents migrated from Russia in 1899. It was a natural nostalgia of looking at the ‘good old days’. The new generation of youth was not giving up Russian, it said, but it saw value in having an additional channel of communications.

The idea for a journal was first proposed at a Doukhobor youth convention of the Union of Doukhobors of Canada (UDC), December 28-29, 1953 in Canora, Saskatchewan. At that time an elder suggested ‘Let’s start a paper’. Two of the youth present, Koozma J. Tarasoff and Nick W. Sherstobitoff, were first year students at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. Both were the obvious choice to undertake this project. Nick’s Dad (William P. Sherstobitoff) and Koozma’s Dad (John K. Tarasoff) were active members of the UDC and of course were anxious that their offspring become active in the movement.

The Doukhobor Inquirer and its shortened version The Inquirer was chosen because the editors felt that the name was most descriptive of young pliable minds that are eager to seek new horizons by transcending sectarian, political and other boundaries.

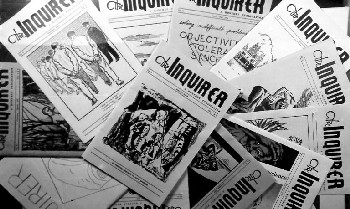

The first issue came out in February 1954 in the form of mimeographed sheets stapled together – five pages in all. In the sixth issue, the monthly changed to a standard 8 ½” by 11” stapled format, in February 1955 it became a folded foolscap edition, and finally in June 1956 The Inquirer went Big Time and was printed with full typeset format in an attractive 6 ½” by 9 ½” professional edition. The journal ceased publication in September 1958 with 1000 copies being printed at its height of which 450 were paid subscribers.

Even though the physical shape changed over the years, the inquiring spirit continued to grow in scope and depth, always striving for a global perspective with local action.

Co-editor Nick W. Sherstobitoff resigned by the summer of the first year because of pressure from university studies. Koozma J.Tarasoff continued as chief editor. Initially mimeographing, assembling and mailing were done by the Chairman (Stanley Petroff) and Secretary (Nick N. Kalmakoff) of the Union of Doukhobors of Canada in Canora until August of 1954. At that time a Gestetner Duplicator and other supplies were purchased by UDC and The Inquirer was fully relocated to Saskatoon.

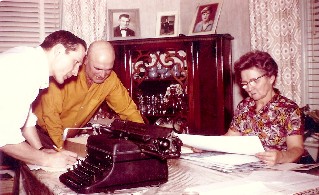

In Saskatoon, the Editor’s Dedushka (grandfather) Koozma J. K. Tarasoff came to the rescue of the young people. He resided next door to his nephew and generously offered his attic as the corporate and publishing office. Dedushka, the parents and others volunteered with the initial printing, addressing and mailing. William P. Sherstobitoff was senior advisor and translator who had a keen mind to search for the truth of a problem. His wife Mary was head typist.

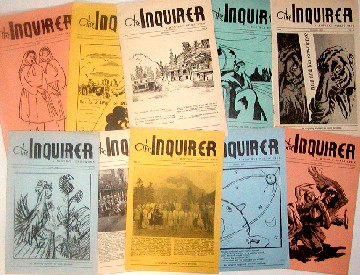

Collage of The Inquirer 1954 – 1958

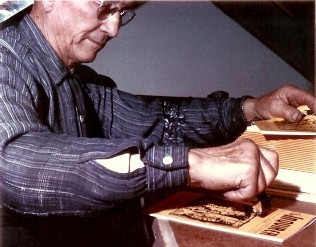

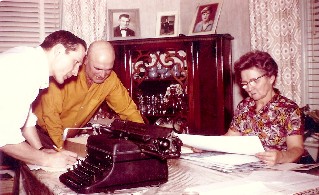

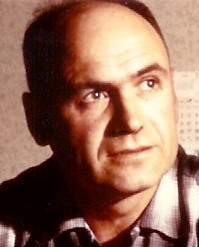

Core staff of The Inquirer in Saskatoon, Sask. 1954. Left to right: Koozma J. Tarasoff, chief editor; William P. Sherstobitoff, senior editor; and Mary Sherstobitoff, head typist.

Other staff members were Alec and Mike Postnikoff, Susan Kalesnikoff, Irene Pereverseff, Joe Popoff, Judy Zaitsoff, Marilyn Verishine, Elaine Malloff, Keith Tarasoff and his sister Donna Tarasoff, and others. Emma Voykin Sawula periodically helped with typing as well as designing several covers. Artists Bill Perehudoff, Frances S. Faminow, Joe Popoff, William Novakshonoff, Harold Popoff and others created our wonderful covers. A number of correspondents across the country topped off the staff. As chief editor, Koozma was also writer, correspondent, at times as artist, business manager and otherwise as organizer of the project from start to finish. All work was donated except for stencil cutting. It was a classic cooperative effort of love.

Lawyer Peter S. Faminow of Vancouver (a graduate from the University of Saskatchewan) was columnist with his provocative satirical ‘Dasha’, ‘Pa Ulitsum’ (Along the Street) as well as ‘Res Ipsa Loquitur’ (It Speaks For Itself). Edith Reeves Solenberger of the Society of Friends (Quakers) in Philadelphia often reviewed books by Quakers that were of interest to the Doukhobors and the wider public. On other occasions, Nick W. Sherstobitoff and his father Bill reviewed books as well. Olga Biryukov of Geneva, the daughter of Pavel Biryukov (biographer of Lev N. Tolstoy), wrote an interesting series on ‘Memoirs of the Life of My Father and Mother’. Peter Bludoff of Blaine Lakes, Sask. occasionally reviewed Russian language vinyl records of Doukhobor and Russian singing. Florence S. Faminow, of Lundbreck, Alberta, then working as an operating nurse in the USA, contributed human interest stories especially for the younger people. A Poetry Corner often brought forth many contributions from the heart. And there was always a sprinkling of Words of Wisdom such as that from Lev Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, George Bernard Shaw, Socrates, and Confucius.

One of the most memorable ‘think’ articles was on Man and His Ideas as well as Life and Work of World Thinkers by Dr Robert Paton, philosophy professor at the University of Saskatchewan. In his earlier life, Dr Paton was a banker, a minister, a lawyer before becoming a philosopher. His Socratic approach to life was informative as well as inspiring to all. He was a model teacher who attracted ordinary citizens to his popular Night Classes, including Koozma’s father who had only three grades of public school education.

A series on ‘Organizations and People Working for a Warless World’ opened the reader’s minds to the wonderful people of the universe who selfishly worked to create a nonkilling society. Groups and individuals included the Quakers, Mennonites, Hutterites, Fellowship of Reconciliation, the Gandhian movement, War Resisters’ International, Bruderhof, Fellowship of Reconciliation, Peaces News, the Christian Pacifist Society of New Zealand, the United Nations, Peace Pilgrim, and the Student Christian Movement.

The Inquirer Features were of the investigative type and often brought forth sharp discussion on the land issue, migration, leadership, zealotry, vegetarianism, war and peace, spiritualism, language use, and the Doukhobor Research Committee.

The Letters to the Editor section was probably the most popular with pros and cons and evaluations of what the reality might be. The letters gave voice to the people who candidly offered feedback on controversial issues of the day that they read in the News section, the Features, the Reports or the Editorials.

Overall, The Inquirer was what the former editor Koozma J. Tarasoff of Ottawa called ‘my second University’ which paralleled his Bachelors of Arts and Sciences studies at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. The experience whetted his appetite to explore anthropology, sociology, ethnology, psychology, and photography as well as to research his ancestors for more than a half a century henceforth. When he resigned his position and went to the West Coast to write a pamphlet on the contributions of Doukhobors to the British Columbia Centennial, there was no one to replace him in Saskatchewan. As there were no moneys to continue, this outstanding pioneering monthly young Doukhobor publication suddenly ceased in the summer of 1958.

Was The Inquirer ahead of its time? Perhaps. As journalists the editors knew that the function of the press is to gather, to make known and to interpret the news of public interest. They knew that news was expected to be true and the comment fair. But no matter what the risk, the press must bear witness to the truth found. Their fearless announcement of truth, as they saw it, made The Inquirer a beacon in a time of intellectual darkness.

Because of this inquiring legacy, the former editor now residing in Ottawa, says: ‘We now have the tools to discuss any topic without prejudice: individual and communal ownership of land, democratic and spiritual leadership, war and peace, religion and atheism, the conscience and the state, patriotism and propaganda, and other sacred cows of society. The world is at stage.’

The mission of peace and universal brotherhood and sisterhood remains the central goal of the Doukhobors. Their testimony against the outward use of force for over two centuries is a confirmation that the taking of human life is contrary to the Spirit of Love and God in each of us. According to Mr. Tarasoff, the Doukhobor message has survived the centuries: ‘We need to get rid of the institution of militarism and wars. Our task is to create the conditions that lead to a nonkilling society.’

Complete copies of The Inquirer are available at the Saskatchewan Archives in Saskatoon, at the Special Collections of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, at Selkirk College in Castlegar, BC. For the general public and the serious researcher, here is a forgotten resource that is pregnant with rich colourful history and pioneering stories that are ready to be rediscovered again in the new millennium.

Press Release – September

20, 2006

SHORT version: 1450 words.

by Koozma J. Tarasoff,

882 Walkley Road, Ottawa, Ontario K1V 6R5 Canada

Email: tarasoff@spirit-wrestlers.com

Phone/fax: (613) 737-5778

SHORT version: 1450 words.

by Koozma J. Tarasoff,

882 Walkley Road, Ottawa, Ontario K1V 6R5 Canada

Email: tarasoff@spirit-wrestlers.com

Phone/fax: (613) 737-5778

The Inquirer Revisited 50 Years Later

Former editor of The Doukhobor Inquirer and current Doukhobor published-author Koozma J. Tarasoff of Ottawa and Andy Conovaloff, a Molokan webmaster from Arizona, USA recently summarized the 1440 items written over 50 years ago and discovered a wealth of rich archival materials that have relevance to our day. Tables of contents for all 50 issues are now posted on the Internet at www.spirit-wrestlers.com in HTML format and as an Excel spreadsheet with keywords and summaries of each article. The original cover designs were added to make this an attractive yet informative research tool for the general public and the serious researcher.Although short-lived, The Inquirer monthly publication in 1954 to 1958 in Canada literally shook the Doukhobor community in North America. As a pioneering journalistic venture, the journal sought fresh ideas and worked to correct the popular inaccurate descriptions of the Doukhobors by the media. Through news reports, feature stories, editorials, satirical columns, human interest stories, book reviews, and Letters to the Editor, the publication fearlessly researched the history of their ancestors.

The Inquirer challenged the notion of leaders claiming special powers of being part ‘of the Divine Right of Kings’. On the basis of early history, its editors discovered that early leader Ilarion Pobirokhin in the 1700s succumbed to the notion of Kings, Queens and Popes to see himself as claiming a primogeniture right to some higher connection to God. His intent was power, paradoxically similar to the takeover of Christendom by Emperor Constantine I. It was early in the 4th century AD that Constantine robbed millions of people from pursuing the spark of God within each person and instead established a Church as a ‘permitted’ religion vested in one institution residing in Rome. The Inquirer reinstated the original notion of the God Within and dispensed with the phantom need for a church hierarchy.

Also The Inquirer challenged the concept of sectarianism. Since the 1895 arms burning, the Doukhobors ceased to be a sect and took on the characteristics of a social movement or a way of life. From the inside, the aim of the Doukhobors became deep, broad, and universal. From the outside, the church and state recognized them as a threat to the existing social order because their ideas were Tolstoyan in nature in that they were against patriotism and self-interest at the expense of others.

A third contribution to the understanding of society was the use of ‘zealotry’ for extremist behaviour. During the mid-1900s, the popular sensationalistic press tended to label all Doukhobors as people having almost genes of violence. The Inquirer challenged this in a study of the press by pointing out that those who participate in arson and bombing are arsonists and bombers. But they are not Doukhobors, even though they hide in hijack manner under the umbrella or cloak of the Doukhobors for protection and legitimacy.

Young people mostly students from the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon as well as High Schools desired to see themselves as worthy citizens in the new emerging society. The Inquirer was the first English language publication of Doukhobors in the world that stimulated its readers to think and question in the manner of Socrates of old: ‘That the unexamined life is not worth living.’

In reaction, some Canadian Doukhobor elders opposed the use of English in the journal. Until then, Russian was considered to be the official language of the group particularly because the elders were still close to the pioneering era when their parents and grandparents migrated from Russia in 1899. It was a natural nostalgia of looking at the ‘good old days’. The new generation of youth was not giving up Russian, it said, but it saw value in having an additional channel of communications.

The idea for a journal was first proposed at a Doukhobor youth convention of the Union of Doukhobors of Canada (UDC), December 28-29, 1953 in Canora, Saskatchewan. At that time an elder suggested ‘Let’s start a paper’. Two of the youth present, Koozma J. Tarasoff and Nick W. Sherstobitoff, were first year students at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. Both were the obvious choice to undertake this project. Nick’s Dad (William P. Sherstobitoff) and Koozma’s Dad (John K. Tarasoff) were active members of the UDC and of course were anxious that their offspring become active in the movement.

The physical shape of the journal changed over the years from mimeographed pages to that of a professional type-set format with 1000 copies printed at its height of which 450 were paid subscribers.

Co-editor Nick W. Sherstobitoff resigned by the summer of the first year because of pressure from university studies. Koozma J.Tarasoff continued as Chief Editor.

In Saskatoon, the Editor’s Dedushka (grandfather) Koozma J. K. Tarasoff invited the youth to set up the corporate and publishing office in his attic. Dedushka, the parents and others volunteered with the initial printing, addressing and mailing. William P. Sherstobitoff was senior advisor and translator who had a keen mind to search for the truth of a problem. His wife Mary was head typist. All work was donated except for stencil cutting. It was a classic cooperative effort of love. As Chief Editor, Koozma was also writer, correspondent, at times as artist, business manager and otherwise as organizer of the project from start to finish.

Saskatoon young people with the help of adults volunteered as staff, including artist Bill Perehudoff who designed several covers. Across the country and abroad, correspondents made their voices known. Lawyer Peter S. Faminow of Vancouver (a graduate from the University of Saskatchewan) was columnist with his provocative satirical ‘Dasha’, ‘Pa Ulitsum’ (Along the Street) as well as ‘Res Ipsa Loquitur’ (It Speaks For Itself). Edith Reeves Solenberger of the Society of Friends (Quakers) in Philadelphia often reviewed books by Quakers that were of interest to the Doukhobors and the wider public. Olga Biryukov of Geneva, the daughter of Pavel Biryukov (biographer of Lev N. Tolstoy), wrote an interesting series on ‘Memoirs of the Life of My Father and Mother’. Peter Bludoff of Blaine Lakes, Sask. occasionally reviewed Russian language vinyl records of Doukhobor and Russian singing. Florence S. Faminow, of Lundbreck, Alberta, then working as an operating nurse in the USA, contributed human interest stories especially for the younger people.

The Inquirer Features were of the investigative type and often brought forth sharp discussion on the land issue, migration, leadership, zealotry, vegetarianism, war and peace, spiritualism, language, and the Doukhobor Research Committee. ‘Man and His Ideas’ as well as ‘Life and Work of World Thinkers’ by Dr Robert Paton, philosophy professor at the University of Saskatchewan, were outstanding ‘think’ pieces.

A series on ‘Organizations and People Working for a Warless World’ opened the reader’s minds to the wonderful people of the universe who unselfishly worked to create a nonkilling society. Groups and individuals included the Quakers, Mennonites, Hutterites, Fellowship of Reconciliation, the Gandhian movement, War Resisters’ International, Bruderhof, Fellowship of Reconciliation, Peaces News, the Christian Pacifist Society of New Zealand, the United Nations, Peace Pilgrim, and the Student Christian Movement.

The Letters to the Editor section was probably the most popular with pros and cons and evaluations of what the reality might be. The letters gave voice to the people who candidly offered feedback on controversial issues of the day that they read in the News section, the Features, the Reports or the Editorials.

When The Inquirer editor left his position and went to the West Coast to write a pamphlet on the contributions of Doukhobors to the British Columbia Centennial, there was no one to replace him in Saskatchewan. As there were no moneys to continue, this outstanding pioneering youth monthly Doukhobor publication suddenly ceased in the fall of 1958.

Was The Inquirer ahead of its time? As journalists the editors knew that the function of the press is to gather, to make known and to interpret the news of public interest. They knew that news was expected to be true and the comment fair. But no matter what the risk, the press must bear witness to the truth found. Their fearless announcement of truth, as they saw it, made them a beacon in a time of intellectual darkness.

Because of this inquiring legacy, today the former editor residing in Ottawa, says: ‘We now have the tools to discuss any topic without prejudice: individual and communal ownership of land, democratic and spiritual leadership, war and peace, religion and atheism, the conscience and the state, patriotism and propaganda, and other sacred cows of society. The world is at stage.’

The Inquirer in Retrospect by Koozma

J. Tarasoff, former Editor.

September 2006. Copyright reserved. The OriginThe idea for a journal was first proposed at a Doukhobor youth convention of the Union of Doukhobors of Canada, December 28-29, 1953 in Canora, Saskatchewan. At that time someone suggested ‘Let’s start a paper’. Two of us, Nick W. Sherstobitoff and myself Koozma J. Tarasoff, were first year students at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. Both of us were present and were the obvious choice to undertake this project. Nick’s Dad (William P. Sherstobitoff [photo right]) and my Dad (John K. Tarasoff [photo right]) were active members of the UDC and of course were anxious that their offspring become the next generation to become active in the Doukhobor movement. We were it!Inexperienced, we began laying plans for the paper. One of the first decisions was the choice of name. The Doukhobor Inquirer and its shortened version The Inquirer was finally chosen because we felt that the name is most descriptive of young pliable minds that are eager to seek new horizons by transcending sectarian, political and other boundaries. The first issue came out in February 1954 in the form of mimeographed sheets stapled together — five pages in all. In the sixth issue, the monthly changed to a standard 8 ½” by 11” stapled format, in February 1955 it became a folded foolscap edition, and finally in June 1956 The Inquirer went Big Time and was printed with full typeset format in an attractive 6 ½” by 9 ½” professional edition. The journal ceased publication in September 1958 with 1000 copies being printed at its height of which 450 were paid subscribers. Even though the physical shape changed over the years, the inquiring spirit, as initially proposed, continued to grow in scope and depth, always striving for a global perspective with local action. My co-editor Nick W. Sherstobitoff resigned by the summer of the first year because of pressure from university studies. While Nick continued to help whenever he could, I served as the chief editor. Mimeographing, assembling and mailing were done by the Chairman (Stanley Petroff [photo right]) and Secretary (Nick N. Kalmakoff [photo right]) of the Union of Doukhobors of Canada in Canora until August of 1954. At that time a Gestetner Duplicator and other supplies were purchased by UDC and The Inquirer was set up in my home town of Saskatoon. It was my Dedushka (grandfather) Koozma J. K. Tarasoff [photo right] who came to our rescue. He resided next door to my parent’s place where I lived and he generously offered his attic as the corporate and publishing office. Dedushka, our parents and others volunteered with the initial printing, the addressing and mailing. William P. Sherstobitoff [photo right] was senior advisor and translator who had a keen mind to search for the truth of a problem. His wife Mary [photo right] was head of the stencil-cutting at this time. [See 1950s story below.] Other staff members were Alec and Mike Postnikoff, Susan Kalesnikoff, Elaine Malloff [photo right], Irene Pereverseff, Joe Popoff, Judy Zaitsoff, Marilyn Verishine [photo right], Keith Tarasoff [photo right] and others. Periodically Emma Voykin Sawula helped with typing. Artists Bill Perehudoff, Frances S. Faminow, Joe Popoff, William Novakshonoff and others created our wonderful covers. A number of correspondents across the country topped off the staff. As chief editor, I was also writer, correspondent, at times as artist, business manager and otherwise as organizer of the project from start to finish. All work was donated except for stencil cutting. It was a classic cooperative effort of love. [See list of authors below.] Lawyer Peter S. Faminow of Vancouver was our columnist with his provocative satirical ‘Dasha’, ‘Pa Ulitsum’ (Along the Street) as well as ‘Res Ipsa Loquitur’ (It Speaks For Itself). Edith Reeves Solenberger of the Society of Friends (Quakers) in Philadelphia often reviewed books by Quakers that were of interest to the Doukhobors and the wider public. On other occasions, Nick W. Sherstobitoff and his father Bill reviewed books as well. Olga Biryukov [photo right] of Geneva, a Tolstoyan and the daughter of Pavel Biryukov (biographer of Lev N. Tolstoy), wrote an interesting series on ‘Memoirs of the Life of My Father and Mother’. Peter Bludoff of Blaine Lakes, Sask. occasionally reviewed Russian language vinyl records of Doukhobor and Russian singing. Florence S. Faminow, of Lundbreck, Alberta, then working as an operating nurse in the USA, contributed human interest stories especially for the younger people. A Poetry Corner often brought forth many contributions from the heart. And there was always a sprinkling of Words of Wisdom from Lev Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, George Bernard Shaw, Socrates, Confucius, and many others. One of the most memorable ‘think’ articles was on ‘Man and His Ideas’ as well as ‘Life and Work of World Thinkers’ by Dr Robert Paton, philosophy professor at the University of Saskatchewan. In his earlier life, Dr Paton was a banker, a minister, a lawyer before becoming a philosopher. His Socratic approach to life was informative as well as inspiring to all of us. And he was a model teacher who attracted ordinary citizens to his popular Night Classes, including my father who had only three grades of public school education. A series on ‘Organizations and People Working for a Warless World’ opened the reader’s minds to the wonderful people of the universe who unselfishly worked to create a nonkilling society. Groups and individuals such as the Quakers, Mennonites, Hutterites, Fellowship of Reconciliation, the Gandhian movement, War Resisters’ International, Bruderhof, Fellowship of Reconciliation, Peace News, the Christian Pacifist Society of New Zealand, the United Nations, Peace Pilgrim, the Student Christian Movement, and others. Our Inquirer Features were of the investigative type and often brought forth much interest on the land issue, migration, leadership, zealotry, vegetarianism, war and peace, spiritualism, the Doukhobor Research Committee, and much more. The Letters to the Editor section was probably the most popular with pros and cons and evaluations of what the reality might be. The letters gave voice to the people who candidly offered feedback on controversial issues of the day that they read in the News section, the Features, the Reports or the Editorials. [See Index of all articles.] Overall, The Inquirer was my ‘second University’ which paralleled my Bachelors of Arts and Sciences studies at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. The experience whetted my appetite to explore anthropology, sociology, ethnology, psychology, and photography as well as to research my ancestors for more than a half a century henceforth. As Seen By An OutsiderIn 1963, Albert Pasqualotto, a Boston College student, USA interviewed me for his paper on The Doukhobor Inquirer. His analysis (pages 6-8) is worth reprinting:‘The Inquirer carried articles on philosophy and religion. It also featured: research reports; book reviews; descriptive accounts of ceremonies, festivals and conventions; recollections of pioneer life and practices; editorials and expressions of opinion. The Inquirer also did cultural promotion for singing, poetry, writing, art and sports. ‘Obstacles and Weaknesses:

The Inquirer throughout its publication life emphasized three ideas:

‘The editor, Koozma J. Tarasoff, spent many long hours researching the history of his ancestors and has become one of the top authorities on Doukhobor history. His one minor fault seems to be that in his efforts to counteract the adverse publicity given the Doukhobors as a whole, he quite naturally tends to the opposite position. But his articles show honesty and careful scholarship. ‘His policy towards the Sons of Freedom is one of giving credit where credit is due and blame where blame is due. He feels that it is unjust to blame the whole group known as the “Sons of Freedom” for the acts of terrorism that have occurred and that the blame should be directed to the responsible individuals. He has also been critical of some of the government’s methods of handling the Sons of Freedom problem. As a result of his views which he voiced in The Inquirer, he has been criticized at times by both Doukhobors and non-Doukhobors.’ As Seen by a DoukhoborPeter G. Makaroff, a prominent Saskatoon lawyer, wrote a ‘Challenge to The Inquirer’ on its third anniversary (Inquirer, vol. 4, nos. 1 & 2, February-March 1957: 9-10), as follows:‘Frankly, I never thought that a Doukhobor periodical in the English language would live to celebrate even its 1st anniversary. I was judging its prospects by the failures of the past along similar lines; by the fate of “The Young Peoples Movement of the Society of Doukhobors”, for example. That was an attempt by our students (High School and University) to organize our youth for social, cultural and religious purposes. It held two successful summer camps — one near Buchanan in 1924 and the other near Petrofka in 1925 — and folded up for keeps. I felt certain, therefore, that the life of The Inquirer would not extend beyond several numbers at the most. To my delight, events have proved me wrong. ‘The remarkable success of The Inquirer has proven, beyond doubt, that we now have at our command a new and most powerful instrument wherewith to grapple our eternal problems and meet the challenge of an ailing civilization. And so on this, its third anniversary, it gives me great pleasure to pay the highest tribute to the initiators and sponsors of The Inquirer for their astuteness in recognizing the need and possibilities of a Doukhobor publication in the English language. Much credit is to its young and talented editor, K. J. Tarasoff, especially and to all those associated with him in any way for the uninterrupted production of a periodical of such excellent caliber over so many years and at such great personal sacrifice to themselves. We owe them a great debt and wish them ever increasing success with this publication in the years that lie ahead. ‘The appearance of The Inquirer as an exponent of the Doukhobor way of life is, to me, most opportune. Every thinking man must recognize that the world was never in more desperate need for workers for peace than today. Never has the human race been faced with greater danger than today. The futility of war and violence was never more apparent. World disarmament, which our simple, illiterate forefathers consistently advocated for centuries, is now readily acknowledged by ever growing numbers as a must if humanity is not to be wiped off the face of the earth by a thermonuclear war that now threatens mankind.’ Peter goes on to challenge The Inquirer to dedicate itself to a crusade for Peace in close cooperation with other historic groups such as Quakers and Mennonites. ‘Such a call will, I am sure, find ready response in many quarters as witness the following excerpt from a recent letter from a prominent Quaker friend: ‘ “We feel that the Doukhobors, as well as Quakers, must learn to pull together and look forward, not backward too much. I have a feeling that our heritage is not something that can be handed down bodily, as an heirloom, but must be reborn in each generation, in each individual, and requires effort, study, and a conscious rejuvenation to make it fit the conditions under which we live. There is too much drifting and reliance on the past and the good name of our fathers. I feel quite strongly about the Doukhobor and Quaker Peace testimony. In the first place, it should grow directly out of a deep and live spiritual experience. The very words Doukhobor and Quaker have their origin in that connection and have no meaning and no message apart from a spiritual life. Therefore, that seems central. I do not feel that a negative peace approach is adequate for our time. We must not only maintain a testimony ‘against’ war, but we need to seek practical ways to ensure peace…”.’ As Analyzed by The EditorCollectively the 50 issues of The Inquirer from the mid-1950s to September 1958 is a good bench-mark of Doukhobor thinking in the world for that era. It was the Golden Age of Inquiry. Doukhobor young people, many attending the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, were full of the energy of youth and were ready to discover new frontiers. They took to heart Socrates maxim: ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’.The inquiring spirit of young people in Saskatchewan was carried across Western Canada on the pages of The Inquirer as well as in inter-visitations and panel discussions with compatriots. The past, the present and the future were all open for public scrutiny and no one could any longer rest on past laurels. Almost immediately, there was reaction to the use of English in communicating the Doukhobor story. Until then, Russian was considered to be the official language of the group particularly because the elders were still close to the pioneering era when their parents and grandparents migrated from Russia in 1899. It was a natural nostalgia of looking at the ‘good old days’. The youth, a new generation, were not giving up Russian, but they saw value in having an additional channel of communications. On the pages of The Inquirer many voices were recorded not only from within the Doukhobor family, but also abroad. The series on the philosophy of ideas and nonviolence opened the readers to the wider world. Following the 1895 arms burning in Russia, Doukhoborism was transformed from sectarianism to that of a social movement. But it took a while for the people to understand this major paradigm shift. As dedicated students, they were keen to understand the roots and essence of the movement. As the opportunity came to give voice to the people, the idea arose that there were more commonalties than differences amongst the group. The question of unity began to percolate on the pages of this pioneering publishing venture. The Union of Doukhobors of Canada (UDC), the Union of Spiritual Communities of Christ (USCC), the Independents, and the zealots were all exposed to the microscope, so to speak. As an expression of Doukhobor thought and a clearing-house of ideas, we had an awesome responsibility to the young as well as the old, to the Doukhobors as well as to non-Doukhobors. When one group sought to glorify its membership, there were enough people to remind us that we are not isolated, but must learn to work with others within and outside the group. The boundaries continued to be flexible and open to dialogue. Was The Inquirer ahead of its time? Perhaps. As journalists we knew that the function of the press is to gather, to make known and to interpret the news of public interest. We knew that news was expected to be true and the comment fair. But no matter what the risk, the press must bear witness to the truth found. Our fearless announcement of truth, as we saw it, made us a beacon in time of intellectual darkness. Because of this inquiring legacy, today we have the tools to discuss any topic without prejudice: individual and communal ownership of land, democratic and spiritual leadership, war and peace, religion and atheism, the conscience and the state, patriotism and propaganda, and other sacred cows of society. The world is at stage…. The mission of peace and universal brotherhood and sisterhood remains as our central goal. The Doukhobor testimony against the outward use of force for over two centuries is a confirmation that the taking of human life is contrary to the Spirit of Love and God in each of us. Our message has survived the centuries: get rid of the institution of militarism and wars. Our task is to create the conditions that lead to a nonkilling society. Complete copies of The Inquirer are available at the Saskatchewan Archives in Saskatoon, at the Special Collections of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, at Selkirk College in Castlegar, BC.; and perhaps other places. For the general public and the serious researcher, here is a forgotten resource that is pregnant with rich colourful history and pioneering ideas that are ready to be rediscovered again in the new millennium. See the complete tables of contents of all 50 issues, with enhanced images of covers. |

The Inquirer (1953-1958), first English-language illustrated publication of the Doukhobors in Canada; it stimulated both young and old to explore their roots and future directions. (Plakun Trava, 1982: 186)  Core staff of The Inquirer, Saskatoon, Sask. 1954. Left to right: Koozma J. Tarasoff, chief editor. William P. Sherstobitoff, senior editor. Mary Sherstobitoff, typist. [Also see photos below] Photo collection by Koozma J. Tarasoff, all rights reserved.

|

Notes on The Inquirer —

The First Doukhobor Publication in the English Language

Compiled by Koozma J. Tarasoff, August 7, 2006. Copyright reserved.The Inquirer

‘The Inquirer began life in February 1954 in mimeograph format in English as the official publication of the Union of Young Doukhobors. Edited by Koozma J. Tarasoff and Nick Sherstobitoff. It's declared purpose was to provide a vehicle for group expression by Doukhobor young people; it was also to serve as a clearing-house for the exchange of ideas and as a bond of unity. In an inspirational exhortation entitled “Time’s bugle calls” in the second issue (March 1954) Eli Popoff wrote:

…our time is insistently

demanding a reformation

so that the reformation of the Middle ages pales

into insignificance…. We, Doukhobor youth, must admit that

for the present we are somewhat stagnating…. But are we

then to stagnate and disintegrate? No! The blood of our

martyred forefathers still runs in our veins. It must and

it will have its

real awakening….

‘The Inquirer indeed attracted free exchange of ideas (including those of radical elements); it provided a forum for interesting debates on the value of formal education, on questions like “What is a Doukhobor?” and “Why are you a Doukhobor?” and whether the Russian language was essential to the continuation of the Doukhobor movement. These issues attracted the participation of prominent members of various communities and persuasions: Nick Kalmakoff, William Soukoreff, Pete Maloff, Walter Lebedoff, Peter Faminow, John G. Bondoreff, N. M. Plotnicove, Jim Kolesnikoff and Norman Rebin, to name but a few, as well as acknowledgment of an appeal from the then Minister of External Affairs, Lester B. Pearson.

‘Non-Doukhobor contributions included Olga Birjukova’s memories of her father Pavel — an early biographer of Lev Tolstoy who was involved in the Doukhobor emigration and visited them in Canada in the 1920s — and book reviews by Edith Reeves Solenberger, an American Quaker whose family still maintains contact with the Doukhobors. In the final issue of 1958, as the publication was about to fold because of financial difficulties, Koozma Tarasoff published an extensive “Report on the Press of British Columbia regarding Doukhobor and Sons of Freedom news”. Mr. Tarasoff has since become a prolific journalist, contributing to or editing numerous publications, as well as providing significant documentation on the Doukhobors to libraries and archives in Canada.’

From Koozma J. Tarasoff’s Spirit Wrestlers: Doukhobor Pioneers’ Strategies for Living (Ottawa, Ontario: Legas Publishing and Spirit Wrestlers Publishing, 2002), the following select quotes from the book:

1. (p.149) William A. Soukoreff [photo above], on the fourth anniversary of The Inquirer wrote:

‘The name, The Inquirer, to many

of us means simply a name of a publication. Yet there is a

deeper meaning that often escapes our minds: namely the

inquiring attitude, with a humanitarian impulse.

‘The recent visit to the Kootenay districts of British Columbia by young people of Saskatchewan, the discussions and exchange of ideas with the Editor and other members of the staff, the technical assistance or occasional correspondence — all this has stimulated thought, thereby increasing an appreciation of The Inquirer.

‘It is commendable that this publication has sought to transcend the dogmatic and the traditional order of our Society, yet at the same time has respected various attitudes of different groups. Even the “Sons of Freedom”, unfortunately barred from communication with other groups, did not escape their inquiry.

‘It is a great task, and not within the scope of a small group, or even a generation, to find the solution for many of our social problems. Nevertheless, the inquiring approach is correct and this is commendable’ (vol. 5, nos. 1 & 2, February-March 1958:20).

‘The recent visit to the Kootenay districts of British Columbia by young people of Saskatchewan, the discussions and exchange of ideas with the Editor and other members of the staff, the technical assistance or occasional correspondence — all this has stimulated thought, thereby increasing an appreciation of The Inquirer.

‘It is commendable that this publication has sought to transcend the dogmatic and the traditional order of our Society, yet at the same time has respected various attitudes of different groups. Even the “Sons of Freedom”, unfortunately barred from communication with other groups, did not escape their inquiry.

‘It is a great task, and not within the scope of a small group, or even a generation, to find the solution for many of our social problems. Nevertheless, the inquiring approach is correct and this is commendable’ (vol. 5, nos. 1 & 2, February-March 1958:20).

2. (p.153) Koozma Tarasoff’s article on William P. Sherstobitoff [photo above], ‘home-grown philosopher with a wide horizon:

‘As editor of this new

journal (including being co-editor with Bill’s son

Nicholas for the first several issues), I…had a close

working relationship with Bill, who served as the senior

advisor, and his spouse Mary who was the main typist. This

publication, in Bill’s view, gave future students pride in

being Doukhobors. The “real impact” for him was on the

outside world as the public began to better understand the

wider and real meaning of the movement itself. The

journal’s logo, “an inquiring approach to social problems”

was an integral and necessary part of the young spirit

that reflected Bill’s thinking and that of a growing

number of young people who considered their place in the

emerging society.

‘The new publication challenged the cult of personality as well as the notion of isolationism. For them, assimilation was not something to be feared, but only managed so that it does not transgress or compromise one’s conscience. This was the time when the zealots became the forerunners of the Hippie movement in Canada that questioned the value of accepted social norms….’

3. (p.255)

Koozma Tarasoff article on his wider family called

Trailblazers.‘The new publication challenged the cult of personality as well as the notion of isolationism. For them, assimilation was not something to be feared, but only managed so that it does not transgress or compromise one’s conscience. This was the time when the zealots became the forerunners of the Hippie movement in Canada that questioned the value of accepted social norms….’

‘When the budding Doukhobor

student journal The

Inquirer was formed, Dad and Dedushka came to its

aid with money and labour. We used Dedushka’s attic as the

“corporate” office, mailing and production room. Besides

generous assistance from young and old, Dad and Dedushka

were my best helpers. With only three grades of public

school education, it was a pleasant surprise when Dad

joined me in a night class on the philosophy of ideas at

the University of Saskatchewan by a brilliant intellectual

Dr Robert Paton….’

4. (p.286) Koozma Tarasoff’s article on the Faminow family called ‘Vision and Hard Work Lifted Barriers of Prejudice’.

‘One of the most interesting

experiences for Peter in his public life was to be elected

as Secretary of Union of Doukhobors of Canada (1957-1958).

Another Doukhobor from Vancouver, Bill Papove, was

President. Both Peter and Bill actively participated in

supporting The Inquirer

publication out of Saskatoon. Peter often had his own

column Pa Ulitsum[Along

the Path] and a satirical Dasha, which provided a forum for Peter

to criticize hypocrisy locally, nationally and

internationally. When the Saskatchewan students led a Tour

of British Columbia in late December 1957, both Peter and

Bill joined in as Socratic type participants….’

Nick W. Sherstobitoff was the co-editor with me in the first months in 1954. Currently he is a supreme court judge in Regina, Sask. 1995 photo by Koozma J. Tarasoff, all rights reserved.

5. (p. 429) Timeline summary:

‘1954-1958. The Inquirer

publication sets a new trend among Doukhobors by

re-evaluating the past and present in the English

language. Its motto: “An inquiring approach to social

problems”. This Saskatoon-based journal helped the wider

public discover some of their misconceptions about the

group by avoiding the tendency to over-generalize on the

basis of isolated acts or non-representative samples of

the population. A report on the press of BC revealed

unjustified bias by the media.’

From Big News! The Inquirer Style Book, compiled and edited by Koozma J. Tarasoff, editor, August 28, 1955, pp. 2-3:

‘The Doukhobor Inquirer

originated at the Union of Young Doukhobor Convention held

in Canora, Sask., December 28-29, 1953. At first two

editors (N. W. Sherstobitoff and K .J. Tarasoff) were

appointed for setting up such a monthly Doukhobor

publication in the English language. After six months,

Nick Sherstobitoff resigned as co-editor because of

pressure from University studies, thus leaving K. J.

Tarasoff sole Editor. Mimeographing, assembling and

mailing were done by the Chairman (Stan Petroff) and

Secretary (Nick Kalmakoff) of the Union of Doukhobors of

Canada until August 1954. At that time a Gestetner

Duplicator and other supplies were bought by the UDC.

Consequently a DI office was set up in Saskatoon. Mrs.

Mary Sherstobitoff is head of the stencil cutting

department. Other local members of the DI staff include

high school and university students, business girls,

interested people and parents. A number of district

correspondents top off the staff.

‘When the DI was first founded at the Youth Convention in 1953, the delegates expressed the hope of reviving and rebuilding the Youth Organization. Thus the DI was to serve as an expression of Doukhobor thought and a “clearing-house” of ideas. Although the Union of Doukhobors of Canada has subsidized the DI, it has in no way restricted the policy of this official publication of the Union of Young Doukhobors.

‘The DI is a non-political publication. By this we do not mean that we can’t mention political parties or governments, — any sphere of human activities may be commended or criticized depending on its action — or lack of it — in the light of an inquiring attitude. Nor would paid advertising influence editorial comment.

‘The function of the press is to gather, to make known and to interpret news of public interest. This, of course, requires great responsibility. The news is expected to be true and the comment fair. But no matter what the risk, the press must bear witness to the truth found. Thus, one of DI’s aims is to continually search for new truths.

‘The DI is not limited to the Doukhobor public, but we feel that it must have universal emphasis. We try to take a positive approach to social and religious problems, whether in the community or world scene. Also we try to be adventurous, that is, to seek new horizons by transcending sectarian or political boundaries. Furthermore, it is working towards making the Doukhobor faith a non-sectarian religion of challenge, rather than an escape. In short, the policy of the DOUKHOBOR INQUIRER is to encourage the lofty ideals of a world view for peace, understanding and good-will for all mankind.

‘Freedom of opinion is granted to anyone, provided that journalistic courtesy is practiced. In the beginning it was not easy to persuade Doukhobors to write, not even in their own paper. When first approached they were inclined to say they couldn’t write anything, never had written anything, didn’t want to write anything – often adding, “I haven’t enough formal or academic education”. However, if you have something to say and can say it clearly, you are really revealing the essence of writing, regardless of your lack of formal education.’

‘When the DI was first founded at the Youth Convention in 1953, the delegates expressed the hope of reviving and rebuilding the Youth Organization. Thus the DI was to serve as an expression of Doukhobor thought and a “clearing-house” of ideas. Although the Union of Doukhobors of Canada has subsidized the DI, it has in no way restricted the policy of this official publication of the Union of Young Doukhobors.

‘The DI is a non-political publication. By this we do not mean that we can’t mention political parties or governments, — any sphere of human activities may be commended or criticized depending on its action — or lack of it — in the light of an inquiring attitude. Nor would paid advertising influence editorial comment.

‘The function of the press is to gather, to make known and to interpret news of public interest. This, of course, requires great responsibility. The news is expected to be true and the comment fair. But no matter what the risk, the press must bear witness to the truth found. Thus, one of DI’s aims is to continually search for new truths.

‘The DI is not limited to the Doukhobor public, but we feel that it must have universal emphasis. We try to take a positive approach to social and religious problems, whether in the community or world scene. Also we try to be adventurous, that is, to seek new horizons by transcending sectarian or political boundaries. Furthermore, it is working towards making the Doukhobor faith a non-sectarian religion of challenge, rather than an escape. In short, the policy of the DOUKHOBOR INQUIRER is to encourage the lofty ideals of a world view for peace, understanding and good-will for all mankind.

‘Freedom of opinion is granted to anyone, provided that journalistic courtesy is practiced. In the beginning it was not easy to persuade Doukhobors to write, not even in their own paper. When first approached they were inclined to say they couldn’t write anything, never had written anything, didn’t want to write anything – often adding, “I haven’t enough formal or academic education”. However, if you have something to say and can say it clearly, you are really revealing the essence of writing, regardless of your lack of formal education.’

The rest of the 20-page booklet deals with the elements of the News Report, the Feature Story, the Law, preparing copy, etc.

In Conclusion

Although short-lived, The Inquirer monthly publication literally shook the Doukhobor community in North America. As a pioneering journalistic effort, the journal sought to bring some fresh ideas to the Doukhobor movement. Its young people desired to see themselves as worthy citizens in the new emerging society. It was the first English language publication of Doukhobors in the world that stimulated its readers to think and question in the manner of Socrates of old: ‘That the unexamined life is not worth living.’

Doukhobors were freethinkers in the early years before their leader Ilarion Pobirokhin in the 1700s succumbed to the notion of Kings, Queens and Popes to see himself as claiming a primogeniture right to some higher connection to God. His intent was power, paradoxically similar to the takeover of Christendom by Emperor Constantine I. It was early in the 4th century AD that Constantine robbed millions of people from pursuing the spark of God within each person and instead established a Church and a ‘permitted’ religion vested in one institution residing in Rome. The Inquirer reinstated the original notion of the God Within and dispensed with the phantom need for a church hierarchy.

Inquirer Statistics

By Andrei

Conovaloff, Webmaster

The Inquirer ran for 4 years 7 months — 50 issues. Near the end, six months were combined into later issues. About 1000 copies were printed per issue. The journal started with 5 pages (graph right), and reached a peak of 58 pages in 2 years. The smallest issue was 4 pages. A total of 1128 pages were published, averaging 23 pages per issue. In total, 1140 articles ran plus many ads and filler quotes and comments.

Though Nick Sherstobitoff resigned as co-editor after six-months leaving the bulk of work upon Tarasoff, there was a core support staff of dozens who submitted news. About 165 Doukhobors (including a Dukh-i-zhiznik presbyter and 2 Tolstoyans) contributed. Only a few, about 10, remained anonymous. These nashi contributed 615 signed articles, about two-thirds of all articles published. Koozma's by-line appeared 193 times, and he signed 4 times as Editor and 50 times as Inquirer. The "Top 10" authors besides Koozma contributed 165 (27%) of the nashi articles:

| Peter

S.

Faminow (37) Nick N. Kalmakoff (19) Olga Biryukov (17) Nick W. Sherstobitoff (16) Peter S. Bludoff (15) |

Frances

Horkoff (14) Michael M. Tomilin (14) William A. Soukoreff (13) Walter P. Strukoff (11) Steve S. Faminow (9) |

A complete list of the Douhobor authors appears below in alphabetical order with the number of signed articles published by each.

156 articles were published from 108 non-Doukhobor authors. Of these, 4 submitted 35 (22%) of the non-Doukhobor articles — Edith Reeves Solenberger(14), Dr. Robert Paton(9), Peter Koltsoff(7), and Esme Wynne-Tyson(5).

87 articles were re-printed from 25 newspapers and newsletters. 61 (70%) came from 4 local newspapers — Nelson Daily News(26), Grand Forks Gazette(14), Saskatoon Star-Phoenix(11), and The Canadian Press(10). One article was reprinted from Iskra, and 2 credited to the USCC — the Community, or Orthodoxy Doukhobors.

For the source of this data, see the Excel spreadsheet file for "Authors-Sources" and "Pages" worksheets (tabs at the bottom).

Douhobor* Authors of Signed Articles and Letters in The Inquirer

|

|

|

1950s — Progressing from "Sect" to "Social Movement"

The 1950s was a pivotal decade for Canadian Doukhobors in which The Inquirer played a significant role. By presenting the Doukhobors in English, The Inquirer communicated with outsiders and invited over 100 outsiders to communicate with Doukhobors. Also it invited younger Doukhobors not fluent in Russian to discuss their heritage. (See: Popular Myths or Fallacies about the Doukhobors #2. Doukhobor is a ‘sect’ or a ‘cult’.)"The Inquirer was founded at

the second and last convention of the Union of Doukhobors

in Canada held in Canora, Saskatchewan, in December, 1953,

when the proceedings were held in English, much to the

protest of many of the elders. The publication forced many

Doukhobors — young and old — to look critically at

themselves in the context of modern times. The USCC Iskra publication

was stimulated to change to a magazine format involving

photographs as a result of The Inquirer challenge, and it forced

non-Doukhobors to re-evaluate their misconceptions of

these people and avoid the tendency to overgeneralize on

the basis of isolated acts or non-representative samples

of the population. The

Inquirer may have been ahead of its time, but for

me as editor the experience directly stimulated me to

undertake a series of studies of the Doukhobors and

ultimately, the preparation of this book." (Plakun Trava, 1982: 186)

About William P. Sherstobitoff:

"The opportunity

of associating with young people continued into the 1950s

with the coming to Saskatoon of prominent students Peter

S. Faminow (who was articling in law) and Peter

Pereversoff (who studied pharmacy and later opened a drug

store in the Prince Albert area). This was also the time

that Bill was chairman of the Union of Doukhobors of

Canada from 1948 to 1954 when its membership included over

4500 Community Doukhobors and 1600 Independents. The

national organization, he recalls, republished the 1909 Zhivotniaia Kniga

Dukhobortsev [Doukhobor Book of Life], and helped to

subsidize the monthly journal of the Union of Young

Doukhobors, The

Inquirer.

"The opportunity

of associating with young people continued into the 1950s

with the coming to Saskatoon of prominent students Peter

S. Faminow (who was articling in law) and Peter

Pereversoff (who studied pharmacy and later opened a drug

store in the Prince Albert area). This was also the time

that Bill was chairman of the Union of Doukhobors of

Canada from 1948 to 1954 when its membership included over

4500 Community Doukhobors and 1600 Independents. The

national organization, he recalls, republished the 1909 Zhivotniaia Kniga

Dukhobortsev [Doukhobor Book of Life], and helped to

subsidize the monthly journal of the Union of Young

Doukhobors, The

Inquirer."As editor of this new journal (including being co-editor with Bill's son Nicholas for the first several issues), I (Koozma J. Tarasoff) had a close working relationship with Bill, who served as the senior advisor, and his spouse Mary who was the main typist. This publication, in Bill's view, gave future students pride in being Doukhobors. The 'real impact' for him was on the outside world as the public began to better understand the wider and real meaning of the [Doukhobor] movement itself. The journal's logo, 'an inquiring approach to social problems' was an integral and necessary part of the young spirit that reflected Bill's thinking and that of a growing number of young people who considered their place in the emerging society. ...

"The new publication challenged the cult of personality as well as the notion of isolationism. For them, assimilation was not something to be feared, but only managed so that it does not transgress or compromise one's conscience. This was the time when the zealots became the forerunners of the Hippie movement in Canada that questioned the value of accepted social norms. The Hippie phenomena was characterized by young people wearing long hair, disrobing, disregarding standard marriage contracts, living in communes, and generally going against the status quo. It was also part of the struggle against militarism and wars, including the Vietnam War that resulted in draft dodgers coming across the US border to Canada. Bill Sherstobitoff was a member of the local Immigrant and Refugee Aid Society with Quakers and others helping these people of conscience find a refuge in this country. (Spirit Wrestlers, 2002: 153)

"Peter gained public

recognition, eventually settled in North Vancouver, ran

for Reeve and almost won, then for seven years served as

an elected Councilor for the North Shore District. He also

ran as an NDP candidate against the incumbent Jack Davies,

Minister of Fisheries; he polled over 12,000 votes and if

it wasn't for 'collusion between the Liberals and

Conservatives, Peter would have won a seat in Parliament.

His position reflected very much the high ground of his

Doukhobor background, 'putting people before machinery'.

Meaning, making machinery as instruments of liberation

rather than man being a slave to machinery.

"Peter gained public

recognition, eventually settled in North Vancouver, ran

for Reeve and almost won, then for seven years served as

an elected Councilor for the North Shore District. He also

ran as an NDP candidate against the incumbent Jack Davies,

Minister of Fisheries; he polled over 12,000 votes and if

it wasn't for 'collusion between the Liberals and

Conservatives, Peter would have won a seat in Parliament.

His position reflected very much the high ground of his

Doukhobor background, 'putting people before machinery'.

Meaning, making machinery as instruments of liberation

rather than man being a slave to machinery."One of the most interesting experiences for Peter in his public life was to be elected as Secretary of Union of Doukhobors of Canada (1957-1958). Another Doukhobor from the Vancouver, Bill Papove, was President. Both and Bill participated in supporting The Inquirer publication out of Saskatoon. Peter often had his own column Pa Ulitsum [Along the Path] and a satirical Dasha, which provided a forum for Peter to criticize hypocrisy locally, nationally and internationally. When the Saskatchewan Students led a Tour of British Columbia in late December 1957, both Peter and Bill joined in as Socratic type participants. While in the Kootenays, they made a fact-finding visit to the New Denver Institution where 170 zealot children were incarcerated. Because of their efforts in finding a face-saving device to the evolving 'genocide', Peter observes that 'we played a tremendous role in that' and within months New Denver was disbanded.

"Another exciting effort of his UDC term was that of organizing the First Non-Violence Conference at the University of British Columbia campus in late June 1958. With a broad base of support from the Fellowship Reconciliation, the Quakers, and Molokans of California, 700 peace activists came out in a bid for a nonviolent approach to problem-solving in our world community. This effort no doubt spurred on other peace manifestations in the 1960s and beyond and helped bring together groups with similar concerns for our survival. (Spirit Wrestlers, 2002: 286)

Doukhobor Timeline — 1950s

(Adapted from Spirit Wrestlers, 2002: pages 428-430, except where indicated.)1950a

USCC develops and eight-year

Russian language program with the assistance of Stephen N.

Petko (who earlier taught 20 years in Kiev, USSR).

1950b

On 14 April, 36 zealots

arrested for burning John J. Verigin's home in Brilliant

BC. Soon after zealots hold a home-burning spree in

Krestova. By the summer 400 zealots are in jail for nudity

and arson, many of them on the basis of confessions alone.

A non-Doukhobor Stefan S. Sorokin arrives and becomes

spiritual guide to the Sons of Freedom; their name is

changed to the Christian Community and Brotherhood of

Reformed Doukhobors.

1950-1952

Hawthorn Research Committee

recommends: recognize Doukhobor marriages in British

Columbia, extend voting, lower penalty for public nudity,

dispose land, relocate zealots, strengthen the educational

program, and appoint a Commission on Doukhobor Affairs.

l953

Judge Lord of Vancouver is

appointed to investigate Doukhobor land sale in BC. In the

summer 400 homes burned, mostly in Krestova area. Homeless

zealots set up 65 tents at Perrys Siding in the Slocan

Valley. Mass arrests follow on 9 September and 148 adults

sent to Vancouver for trial.

1953-1959

Because some parents are

jailed and because others refuse to send children to

school, 170 zealot children are taken by RCMP to New

Denver — an experiment in re-charting children's lives.

This goes against the spirit of the Hawthorn Research

Committee, but it is a political 'get-tough' policy of the

new Premier W.A.C. Bennett. Periodic raids on truant

children become a routine task of the police, as zealots

develop atrocity stories and new myths. Termed as 'a

disastrous failure'.

1954

Author William A. Soukoreff

visits Moscow and Tula. Reviews ties with Doukhobors in

USSR and Tolstoyans; he was the first Canadian Doukhobor

to do this in over two decades.

1954-1958

1955

Canadian Criminal Code

removes the three-year penalty for public nudity.

1956

For BC Doukhobors the

federal and provincial vote is restored (banned in 1919,

1931, and 1934). Voting resumed in 1957.

1957a

Eli A. Popoff becomes first

Doukhobor to hold public office in BC as School Trustee.

Affirmation accepted in lieu of Oath of Allegiance. In the

same year, a modern USCC DOukhobor Community Center is

constructed in Grand Forks.

1957b

Undoubtedly the strongest aspect of Doukhobor ideology is their pacifism. Here, Koozma J. Tarasoff, (second from the left, back row) attends the Triennial Conference of the War Resisters International in London, England, July 1957. (Plakun Trava, 1982: 233)

1957, December

"Building bridges of understanding" was the theme of this historic meeting of Saskatchewan youth [Independent Doukhboors] with British Columbia youth [Community Doukhobors], December 1957. The occasion was a panel discussion in Grand Forks, B.C. From left to right, the first nine members of the visiting group include: Joe M. Postnikoff, Saskatoon, Sask.; Nick W. Sherstobitoff, Saskatoon; Peter F. Chernoff Blaine Lake, Sask.; Norman K. Rebin, Blaine Lake, Sask.; Koozma J. Tarasoff, Saskatoon, Sask.; Peter S. Faminow, Vancouver, B.C.; Wm. P. Sherstobitoff, Saskatoon, Sask.; Miss Winnifred W. Horkoff, Kamsack, Sask.; and William N. Papove Burnaby, B.C. The remainder are hosts in Grand Forks, B.C.; Peter Soloveoff (chairman); Eli A. Popoff; John K. Nevokshonoff; Peter M. Gritchin; John J. Semenoff, and Jim D. Kolesnikoff. The group also discussed: "Where Do We Go From Here? — a discussion on the future of the Doukhobor movement". (Plakun Trava, 1982: 186) This historic youth tour in December included panel discussions on issues of the day, slide shows and talks of trip to Europe, a stage play, banquets, socials, tours, visits, and choral performances.("Young Adult Tour of Western Canada," The Inquirer, December 1957, page 8.)

1958, June

On June 27-29 the Peace Through Nonviolence Conference is held at the University of British Columbia, jointly by Doukhobors, Quakers, Fellowship of Reconciliation, and California Molokans [Jumpers]. Sundry Photos, Vancouver, BC, recorded this major success story. A program was published. Click on photo to enlarge. In front, left to right are the organizers: Peter S. Faminow, Mildred Fahrni, and William N. Papove. Peter was secretary- treasurer of the Union of Doukhobors of Canada, while William was the President. Mildred Fahrni was Western head of the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Several groups are shown. On the left, front row, are mostly Molokan-Jumpers from California in distinct dress. On the right, are Doukhobor youth choirs in uniform traditional dress. Scattered are mostly Doukhobors, men in coat and tie, women with head-scarfs.